Heart valve

A heart valve normally allows blood flow in only one direction through the heart. The four valves commonly represented in a mammalian heart determine the pathway of blood flow through the heart. A heart valve opens or closes incumbent upon differential pressure on each side.[1][2][3]

The four valves in the heart are:[4]

- The two atrioventricular (AV) valves, which are between the atria and the ventricles, are the mitral valve and the tricuspid valve.

- The two semilunar (SL) valves, which are in the arteries leaving the heart, are the aortic valve and the pulmonary valve.

A form of heart disease occurs when a valve malfunctions and allows some blood to flow in the wrong direction. This is called regurgitation.

Contents |

Atrioventricular or cuspid valves

These are small valves that prevent backflow from the ventricles into the atrium during systole. They are anchored to the wall of the ventricle by chordae tendineae, which prevent the valve from inverting.

The chordae tendineae are attached to papillary muscles that cause tension to better hold the valve. Together, the papillary muscles and the chordae tendineae are known as the subvalvular apparatus. The function of the subvalvular apparatus is to keep the valves from prolapsing into the atria when they close. The subvalvular apparatus have no effect on the opening and closure of the valves, however. This is caused entirely by the pressure gradient across the valve. The peculiar insertion of chords on the leaflet free margin however provides systolic stress sharing between chords according to their different thickness.[5]

The closure of the AV valves is heard as the first heart sound (S1).

Mitral valve (bicuspid)

Also known as the "bicuspid valve" because it contains two flaps, the mitral valve gets its name from the resemblance to a bishop's mitre (a type of hat). It allows the blood to flow from the left atrium into the left ventricle. It is on the left side of the heart and has two cusps.

A common complication of rheumatic fever is thickening and stenosis of the mitral valve.

Tricuspid valve

The tricuspid valve is the three-flapped valve on the right side of the heart, between the right atrium and the right ventricle which stops the backflow of blood between the two. It has three cusps.

Semilunar valves

These are located at the base of both the pulmonary trunk (pulmonary artery) and the aorta, the two arteries taking blood out of the ventricles. These valves permit blood to be forced into the arteries, but prevent backflow of blood from the arteries into the ventricles. These valves do not have chordae tendineae, and are more similar to valves in veins than atrioventricular valves.

Aortic valve

The aortic valve lies between the left ventricle and the aorta. The aortic valve has three cusps. During ventricular systole, pressure rises in the left ventricle. When the pressure in the left ventricle rises above the pressure in the aorta, the aortic valve opens, allowing blood to exit the left ventricle into the aorta. When ventricular systole ends, pressure in the left ventricle rapidly drops. When the pressure in the left ventricle decreases, the aortic pressure forces the aortic valve to close. The closure of the aortic valve contributes the A2 component of the second heart sound (S2).

The most common congenital abnormality of the heart is the bicuspid aortic valve. In this condition, instead of three cusps, the aortic valve has two cusps. This condition is often undiagnosed until the person develops calcific aortic stenosis. Aortic stenosis occurs in this condition usually in patients in their 40s or 50s, an average of over 10 years earlier than in people with normal aortic valves.

Pulmonary valve

The pulmonary valve (sometimes referred to as the pulmonic valve) is the semilunar valve of the heart that lies between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery, and has three cusps. Similar to the aortic valve, the pulmonary valve opens in ventricular systole, when the pressure in the right ventricle rises above the pressure in the pulmonary artery. At the end of ventricular systole, when the pressure in the right ventricle falls rapidly, the pressure in the pulmonary artery will close the pulmonary valve.

The closure of the pulmonary valve contributes the P2 component of the second heart sound (S2). The right heart is a low-pressure system, so the P2 component of the second heart sound is usually softer than the A2 component of the second heart sound. However, it is physiologically normal in some young people to hear both components separated during inhalation.

Heart valve dynamics

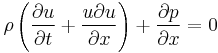

In general, motion of the heart valves is determined using the Navier-Stokes equation; using boundary conditions of the blood pressures, pericardial fluid, and external loading as the constraints.

Motion of the heart valves is used as a boundary condition in the Navier-Stokes equation in determining the fluid dynamics of blood ejection from the left and right ventricles into the aorta and the lung.

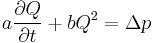

Relationship between pressure and flow in open valves

The pressure drop,  , across an open heart valve relates to the flow rate, Q, through the valve:

, across an open heart valve relates to the flow rate, Q, through the valve:

If:

-Inflow energy conserved

-Stagnant region behind leaflets

-Outflow momentum conserved

-Flat velocity profile

Valves with a single degree of freedom

Usually the aortic and mitral valves are incorporated in valve studies within a single degree of freedom. These relationships are based on the idea of the valve being a structure with a single degree of freedom. These relationships are based upon the Euler equations.

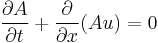

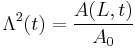

Equations for the aortic valve in this case:

![A(x,t) = A_0 \left(1-[1-{\Lambda}(t)]{x\over{L}}\right)^2](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/69cfb1e048f067f52932a3dffa341fb8.png)

![\int_{0}^{L} p(x,t) {{\partial}A\over{\partial}x}\, dx = [A_0 - A(L,t)]p(L,t)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a49e2182a70c455ff1810142f82bd6c5.png)

where:

u=axial velocity

p=pressure

A=cross sectional area of valve

L=axial length of valve

(t)=single degree of freedom; when

(t)=single degree of freedom; when

See also

- ^ "Heart Valves". Heart and Stroke Encyclopedia. American Heart Association, Inc. http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=4598. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ^ Klabunde, RE (2009-07-02). "Pressure Gradients". Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts. Richard E. Klabunde. http://www.cvphysiology.com/Hemodynamics/H010.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-06.

- ^ Klabunde, RE (2007-04-05). "Cardiac Valve Disease". Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts. Richard E. Klabunde. http://www.cvphysiology.com/Heart%20Disease/HD003.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-06.

- ^ not counting the valve of the coronary sinus, and the valve of the inferior vena cava

- ^ J Cardiovasc Surg (Turin) 2000 Apr;41(2):193-202 video

- Artificial heart valve

- Cardiac fibrosis

- Congenital heart disease

- Disorders of the valves (Valvular heart disease)

- Aortic valve disorders:

- Mitral valve disorders

- Pulmonary valve disorders

- Tricuspid valve disorders

- Endocarditis

- Heart sounds

- Bjork–Shiley valve

Notes

- ^ "Heart Valves". Heart and Stroke Encyclopedia. American Heart Association, Inc. http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=4598. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ^ Klabunde, RE (2009-07-02). "Pressure Gradients". Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts. Richard E. Klabunde. http://www.cvphysiology.com/Hemodynamics/H010.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-06.

- ^ Klabunde, RE (2007-04-05). "Cardiac Valve Disease". Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts. Richard E. Klabunde. http://www.cvphysiology.com/Heart%20Disease/HD003.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-06.

- ^ not counting the valve of the coronary sinus, and the valve of the inferior vena cava

- ^ J Cardiovasc Surg (Turin) 2000 Apr;41(2):193-202 video

External links

- Mitral Valve Repair at The Mount Sinai Hospital – "Mitral Valve Anatomy"]

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- ^ "Heart Valves". Heart and Stroke Encyclopedia. American Heart Association, Inc. http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=4598. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ^ Klabunde, RE (2009-07-02). "Pressure Gradients". Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts. Richard E. Klabunde. http://www.cvphysiology.com/Hemodynamics/H010.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-06.

- ^ Klabunde, RE (2007-04-05). "Cardiac Valve Disease". Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts. Richard E. Klabunde. http://www.cvphysiology.com/Heart%20Disease/HD003.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-06.

- ^ not counting the valve of the coronary sinus, and the valve of the inferior vena cava

- ^ J Cardiovasc Surg (Turin) 2000 Apr;41(2):193-202 video